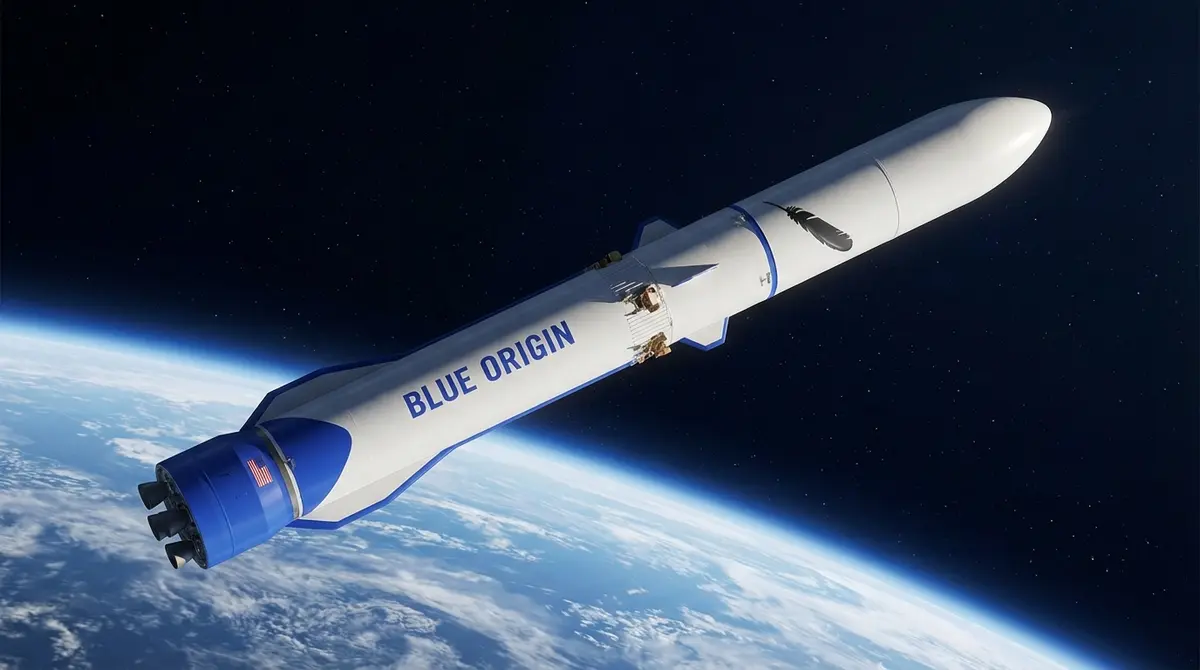

The question of whether Blue Origin will pursue a fully reusable launch vehicle has surfaced once again. According to a new report, a recent job posting suggests that the internal debate regarding New Glenn’s second stage (GS2) may be swinging back toward a reusable architecture. This development marks the latest turn in a long-running strategic "horse race" within the company, as it seeks to optimize the economics and operability of its heavy-lift rocket.

What Is the ‘Horse Race’ for New Glenn’s Second Stage?

For years, Blue Origin has maintained a dual-track approach to the development of its upper stage. While the first stage of New Glenn is designed to be fully reusable—landing on a sea-based platform after launch—the second stage has faced a more complex identity crisis. Publicly, the company has baselined an expendable second stage for the vehicle’s initial flights, prioritizing performance and schedule.

However, the company has never fully abandoned the dream of full reusability. In previous interviews, leadership described an internal competition described as a "horse race." One team was tasked with making the expendable stage so inexpensive to manufacture that reuse would not be economically viable. Simultaneously, a second team was challenged to make a reusable stage—often referred to internally under the moniker "Project Jarvis"—so operable and efficient that expending hardware would make no sense. This latest job posting indicates that the reusable faction may be gaining fresh momentum.

Why Is Second Stage Reuse So Difficult?

Recovering a second stage is significantly harder than recovering a booster. While a first stage separates at lower velocities and altitudes, the second stage must accelerate the payload all the way to orbital velocity (over 17,500 mph). To return, it must survive the intense heat of atmospheric reentry, which requires heavy thermal protection systems (heat shields) and additional structure.

This added weight creates a "payload penalty." Every kilogram of heat shield, landing gear, and reserve fuel added to the upper stage is a kilogram of payload capacity lost. For Blue Origin, the challenge has been engineering a reusable GS2 that can survive reentry without cannibalizing the rocket’s ability to deliver heavy satellites to orbit. The debate has often centered on materials, with engineers oscillating between lightweight aluminum-lithium structures for expendable variants and robust stainless steel for reusable prototypes.

Get our analysis in your inbox

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.